Volume: 22 Issue: 4 April 2024 - Supplement - 4

FULL TEXT

The first living donor kidney transplant in Syria was performed 44 years ago; by the end of 2022, 6265 renal transplants had been performed in Syria. Kidney, bone marrow, cornea, and stem cells are the only organs or tissues that can be transplanted in Syria. Although 3 heart transplants from deceased donors were performed in the late 1980s, cardiac transplant activities have since discontinued. In 2003, national Syrian legislation was enacted authorizing the use of organs from living unrelated and deceased donors. This important law was preceded by another big stride: the acceptance by the higher Islamic religious authorities in Syria in 2001 of the principle of procurement of organs from deceased donors, provided that consent is given by a first- or second-degree relative. After the law was enacted, kidney transplant rates increased from 7 per million population in 2002 to 17 per million population in 2007. Kidney transplants performed abroad for Syrian patients declined from 25% in 2002 to <2% in 2007. Rates plateaued through 2010, before the political crisis started in 2011. Forty-four years after the first successful kidney transplant in Syria, patients needing an organ transplant rely on living donors only. Moreover, 20 years after the law authorizing use of organs from deceased donors, a program is still not in place in Syria. The war, limited resources, and lack of public awareness about the importance of organ donation and transplant appear to be factors inhibiting initiation of a deceased donor program in Syria. A concerted and ongoing education campaign is needed to increase awareness of organ donation, change negative public attitudes, and gain societal acceptance. Every effort must be made to initiate a deceased donor program to lessen the burden on living donors and to enable national self-sufficiency in organs for transplant.

Key words : Brain death, End-stage kidney disease, Middle East, Organ shortage, Organ transplantation, Survey

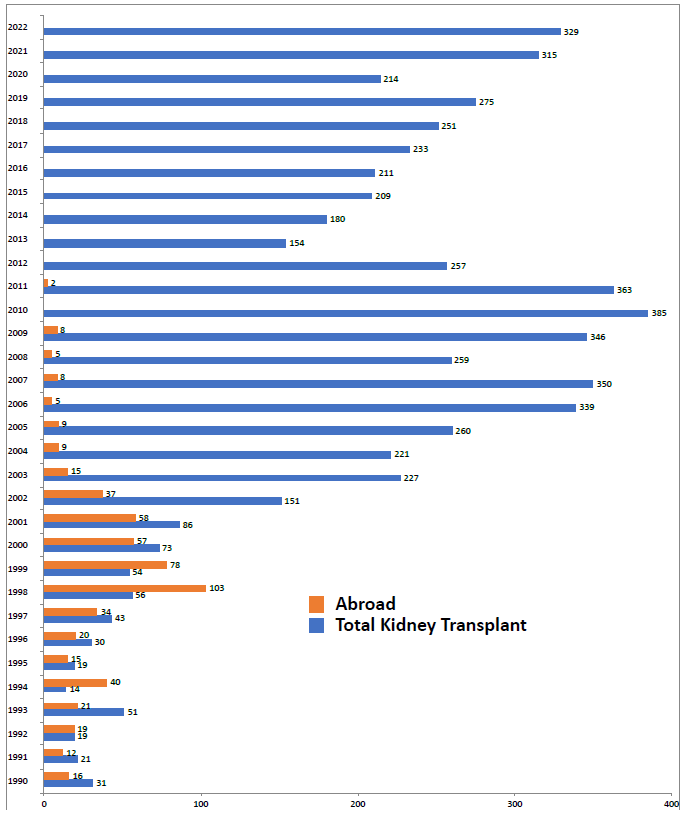

Introduction Syria has a long-standing transplant history; the first successful kidney transplant in Syria was performed at Harasta Hospital in Damascus in 1979. By 2022, 6265 kidney transplants had been performed. There are 8 kidney transplant centers among the 3 largest cities. The current regular transplant programs in Syria include kidney, bone marrow, imported cornea, and stem cells.1 A few years ago, 2 liver transplants from living donors were done at Al Assad University Hospital in Damascus. Interestingly, a deceased donor program did exist more than 3 decades ago: 3 heart transplants from deceased donors were performed at Tishreen Military Hospital in Damascus between mid-1989 and the end of 1990; however, cardiac transplant activities have since been discontinued.2 Legislation, known as Law Number 30, was enacted in 2003, authorizing the use of organs from deceased donors, as well as from altruistic, living, nonrelated donors. A national guidance on organ transplant has been instituted that states organ donation must be based on motivations involving only Syrian nationals (that is, a non-Syrian donor cannot donate to a Syrian patient and a Syrian donor cannot donate to a non-Syrian patient). This legislation is considered a landmark in the history of organ transplant in Syria because it recognized, for the first time, the concept of brain death and the authorization of retrieving organs from deceased donors.3 After this new legislation went into effect, rate of kidney transplants increased substantially over the next 5 years, from 7 per million population (pmp) in 2002 to 17 pmp in 2007.4 During the same period, kidney transplants performed abroad for Syrian patients significantly declined, from 25% in 2002 to <?2% in 2007 (Figure 1).

However, between 2007 and when the war in Syria began in March 2011, kidney transplant rates did not increase.5 Little is known about the reasons behind the plateau of renal transplant rates during the prewar years, but it is likely the persistent, exclusive reliance on living donors and, more importantly, the delay in establishing a deceased donor program, which is widely considered an essential component to respond to organ shortages, were key factors. In November 2009, the Ministry of Health established The Syrian National Center for Organ Transplantation with the objectives to have a deceased donation program get underway in Syria, to curtail living unrelated transplants, and to help initiate, supervise, and coordinate activities between donor hospitals and transplant centers. Establishment of these objectives would have meant ending the practice of kidney transplants from living unrelated donors. Unfortunately, this center remains inactive to this day.

The war in Syria, which started in 2011, has reinforced the reasons that prevented the start of a deceased donor program before the conflict. The war has dramatically affected patients and health services, including all aspects of organ transplant, damaging existing programs and thus depriving the nation of what has already been achieved, and, importantly, paralyzing new projects. Particularly affected was the liver transplant initiative. At the beginning of 2011, the government of Syria was taking steps to initiate a liver transplant program, including cooperation with Brazilian and Iranian liver transplant centers, where specialized teams were sent for training. With the war underway, the trainers from those countries could not visit Syria, and the project came to a halt. The kidney transplant program was also severely affected by the war, especially during the first 3 years (from 2011 to 2013), when the kidney transplant rate decreased by 60% (from 17 pmp in 2010 to 6 pmp in 2013). However, this rate has again increased over the next 9 years (from 2014 to 2022) to reach 18.3 pmp in 2022 (329 kidney transplants) for a population of 18 million compared with 23 million before the war began. We noticed a decreased rate to 11.9 in 2020 because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Unfortunately, 20 years after the law authorizing use of deceased donor organs, a program is still not in place in Syria, and all transplant activities rely only on living donors.

Obstacles to Initiating a Deceased Organ Donation Program in Syria

Initiating a deceased donor organ donation program is widely considered an essential component of a comprehensive approach to respond to the ever-increasing organ shortages worldwide. Nevertheless, transplantation in the Middle East is shaped by the prevailing religious, socioeconomic, and health indicators in the different countries.6 Living donor organ donation is the most widely practiced type of donation in the Middle East. However, some countries, including Iran, Turkey, Kuwait, and Saudi Arabia, have active deceased donor programs. Ignorance appears to be a major limiting factor inhibiting the initiation of a deceased donor program in Syria, as in many other developing countries.7 The indifferent attitude of health care professionals has also been identified as a limiting factor to initiating a deceased donor transplant program in Syria, a fact that has also been pointed out in other developing countries.7,8 Other obstacles to initiating deceased donor organ donation in Syria include, among others, limited resources; low health spending; poorly developed infrastructures; inadequate dialysis programs; few organized teams of transplant surgeons and nephrologists; organ-selling practices; the lack of public awareness, education, and motivation for organ donation; and the issue of the definition of brain death. However, some transplant professionals in Syria and elsewhere in the Middle East argue that the striking differences in the rates of deceased donor organ donation between countries are only partially explained by the aforementioned factors and that other cultural and social reasons could also be among the obstacles.9

One obstacle to a deceased donor organ donation program that is less well appreciated is religious concerns. Most major faiths and religions in Syria encourage donation. However, skepticism remains among some scholars of Islam, often relating to the concept of brain death and/or the processes surrounding death itself. “Whosoever saves the life of one person, it would be as if he saved the life of all mankind.” This Qur’an passage highlights a key principle of Islam, according to which organ transplant is considered entirely in keeping with the faith.

In light of this correct understanding of Islam, the Ministry of Islamic Affairs in Syria announced in 2001 its approval of the principle of procurement of organs from deceased donors, provided that consent is given by a first- or second-degree relative of the donor.5 In 1996, the United Kingdom Muslim Law Council ruled that organ transplant is in keeping with Islam10; other similarly proactive declarations have emerged elsewhere. Nonetheless, and despite repeated attempts by Islam scholars to promote organ donation, many individual Muslims from across the Middle East are still reluctant to accept the concept, particularly that of deceased donor organ donation.11

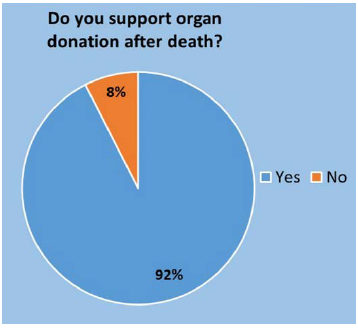

Successful organ donation depends on multiple factors, such as legislation, which helps to develop the process, and agencies that put the guidelines into practice. However, whatever the system, health professionals’ beliefs and attitudes play a major role in helping make this happen.12 To gain an understanding of health professionals’ level of knowledge about and attitude toward organ donation and transplant, an electronic survey was conducted in January 2020 involving a nationally representative sample of 213 health care providers, including almost all transplant physicians and surgeons in Syria. Interestingly, 86% of the respondents said they are sufficiently informed about organ donation programs and 92% support organ donation after death (Figure 2). This is a high percentage that should be cause for optimism. The message from this survey is that one could speculate that the delay in establishing a deceased donor program is not due to the health professionals’ lack of acceptance of organ donation after death but mostly the inaction and indifference of the stakeholders.

There is an ongoing debate in Syria about whether to start a deceased organ donor program or to keep relying only on living organ donors. As noted previously, in 2003, the Law Number 30 was enacted, authorizing the use of organs from volunteer unrelated donors and deceased donors. Despite the positive aspects of this law, the most important of which was the contribution of unrelated donors to substantially increase the number of transplants in the country, the negative aspects were also obvious. The poor used the law to sell their organs to the rich, and this model is in violation of the Istanbul Declaration.13 Therefore, living unrelated kidney donation in effect became a hindrance to establishing a deceased organ donor program because it masked the need and decreased the urge to start a national deceased donor program at the expense of tarnishing the reputation of transplantation among ordinary people.14

The threat is the recently changing geopolitics and shifted economy, which has had a negative effect by increasing the selling of organs on the black market. Last, but not least, the war continues to add substantially to the many reasons that have prevented the start of a deceased donor program before the conflict.

The Way Forward for Establishing a Deceased Donor Program in Syria

Unfortunately, 20 years after the law authorizing organ donation by deceased donors, a program is still not in place in Syria. The opportunity lies in investing in the existing models of organ donation, incorporation of the acceptance of higher Islamic religious authorities, and actions from governmental legislation, media, and technology to increase awareness at large of transplantation. There is a need for a concerted and ongoing education campaign by the transplant community and the public to increase awareness of organ donation, with an aim to change negative public attitudes and to gain societal acceptance. It is worthwhile for transplant teams to be broadly aware of the issues and also to be mindful of resources for counseling. We believe that increased awareness of these issues within the transplant community will enable us to discuss these openly with patients, if they wish. A deceased organ donor program has the potential to widen the donor pool, but it needs acceptance. In addition, further improvements of the legal framework are needed; for example, is it better for a society like ours to move toward presumed consent rather than informed consent provided by law? This is an example out of several proposals to amend the transplant law that are the subject of debate in the medical community. Additional engagement and evaluation of the systems by stakeholders are required to provide insight into best practices that will help improve transplant rates and services.

Moreover, there is a need to establish national renal registries to provide valuable information on end-stage renal disease, particularly on sociodemographics, risk factors, treatment modalities, and outcomes. Achieving national self-sufficiency does require effort, investment, and commitment by the government, medical professionals, and communities. Several examples from our area confirm that such efforts are possible in the most challenging circumstances.

Conclusions

More than 4 decades after the first successful renal transplant in Syria, patients still must rely on living donors only. Every effort must be made to initiate a deceased donor program to lessen the burden on living donors and to enable a national self-sufficiency not only in kidney transplant but in transplant of all other organs. The awareness of the public, the medical community, and the government about the importance of initiating a deceased donor program in Syria is indispensable to overcome the current threats.

References:

- Saeed B. The effect of the Syrian crisis on organ transplantation in Syria. Exp Clin Transplant. 2015;13(2):206-208. doi:10.6002/ect.2014.0287

CrossRef - PubMed - Saeed B. How did the war affect organ transplantation in Syria? Exp Clin Transplant. 2020;18(Suppl 1):19-21. doi:10.6002/ect.TONDTDTD2019.L23

CrossRef - PubMed - Saeed B, Derani R, Hajibrahim M, et al. Volume of organ failure in Syria and obstacles to initiate a national cadaver donation program. Iran J Kidney Dis. 2008;2(2):65-71.

CrossRef - PubMed - Saeed B. Current challenges of organ donation programs in Syria. Int J Organ Transplant Med. 2010;1(1):35-39.

CrossRef - PubMed - Saeed B. Development of solid organ transplantation in Syria. Int J Organ Transplant Med. 2011;2(1):40-46.

CrossRef - PubMed - Ali A, Hendawy A. Renal transplantation in the Middle East: strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats [SWOT] analysis. Urol Nephrol Open Access J. 2015;(2)33-35. doi:10.15406/unoaj.2015.02.00028

CrossRef - PubMed - Cheng IK. Special issues related to transplantation in Hong Kong. Transplant Proc. 1992;24(6):2423-2425.

CrossRef - PubMed - Naqvi SA, Rizvi SA. Renal transplantation in Pakistan. Transplant Proc. 1995;27(5):2778.

CrossRef - PubMed - Oliver M, Ahmed A, Woywodt A. Donating in good faith or getting into trouble: religion and organ donation revisited. World J Transplant. 2012;2(5):69-73. doi:10.5500/wjt.v2.i5.69

CrossRef - PubMed - Golmakani MM, Niknam MH, Hedayat KM. Transplantation ethics from the Islamic point of view. Med Sci Monit. 2005;11(4):RA105-RA109.

CrossRef - PubMed - Einollahi B. Cadaveric kidney transplantation in Iran: behind the Middle Eastern countries? Iran J Kidney Dis. 2008;2(2):55-56.

CrossRef - PubMed - Alsaied O, Bener A, Al-Mosalamani Y, Nour B. Knowledge and attitudes of health care professionals toward organ donation and transplantation. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2012;23(6):1304-1310. doi:10.4103/1319-2442.103585

CrossRef - PubMed - Alrukhami M, Chapman J, Delmonico D, et al. The declaration of Istanbul on organ trafficking and transplant tourism. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3(5):1227-1231. doi:10.2215/CJN.03320708

CrossRef - PubMed - Saeed B. The impact of living-unrelated transplant on establishing deceased-donor liver program in Syria. Exp Clin Transplant. 2014;12(5):494-497. doi:10.6002/ect.2014.0164

CrossRef - PubMed

Volume : 22

Issue : 4

Pages : 28 - 32

DOI : 10.6002/ect.BDCDSymp.L10

From the Farah Association for Child with Kidney Disease, Damascus, Syria

Acknowledgements: The author has no sources of funding for this study and has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Corresponding author: Bassam Saeed, Farah Association for Child with Kidney Disease, Deputy chair of the ISN Middle East Regional Board, PO Box 8292, Damascus, Syria

Phone: +963 11 3340766

E-mail: bmsaeed2000@yahoo.com

Figure 1. Total Kidney Transplants Performed in Syria Compared With Number of Kidney Transplants Performed Abroad for Syrians (1990-2022)

Figure 2. Survey of Perspective of Health Professionals in Syria About Organ Donation After Death