Volume: 18 Issue: 1 January 2020 - Supplement - 1

FULL TEXT

Objectives: Living donors endure several challenges throughout the organ donation process. Physically related effects are further compounded by social and emotional challenges. To date, no previous studies have addressed the motives and impact of organ donations from living donors in Jordan.

Materials and Methods: We conducted a qualitative exploratory study to understand the experiences of a random sample of genetically and legally related living donors in Jordan. Participants were identified through the Directorate of the Jordanian Center for Organ Transplantation database. Our sample included Jordanians and non-Jordanians who donated a kidney or liver. Most data were collected by phone interviews with living donors; some donors were personally interviewed. Donors were asked about their experiences during the periods before and after the process of donation, including their feelings, emotions, and motives. Interviews were analyzed using the thematic analysis approach.

Results: In total, 360 participants (337 kidney and 23 liver donors; 290 Jordanians and 70 non-Jordanians) completed the interview. The time from donation to interview ranged from 14 days to 7 years. The period before donation was characterized by fear and confusion. After donation, most donors described a positive emotional state that was marked by self-satisfaction, pride, and increased support of organ donation. However, many stated that they felt forgotten. Most donors were motivated by social solidarity, and others invoked the role of their religious beliefs as the main motive. Other motives included improving the recipient’s life and fear that patients would be abandoned.

Conclusions: The emotional distress of living donors during the predonation period emphasizes the need for social and psychological support in addition to medical evaluations. Donors who had positive experiences with donation can play a role in advocating for donation. Finally, in Jordan, social solidarity and religious beliefs are the most important factors that motivate donation.

Key words : Experiences, Feelings, Motives

Introduction

Similar to that shown in the rest of world, the rates of living-donor transplant in Jordan have steadily increased. For living-donor kidney transplant, 29 procedures per million population have been performed per year in Jordan.1

Throughout the transplant process, living donors endure a number of challenges. Physically related effects are further compounded by social and emotional challenges. Psychological conditions can significantly affect the outcomes of the donation process in living donors.2 There have been no previous studies that have addressed the motives and impact of organ donation on living donors in Jordan.

Materials and Methods

We conducted a qualitative exploratory study to understand the experiences of a random sample of living donors in Jordan. Participants were identified through the Directorate of the Jordanian Center for Organ Transplantation database. Our sample included Jordanians and non-Jordanians who donated a kidney or liver in Jordan. The time of the donation ranged from 14 days to 7 years before the interview, and interviews were performed between January 2017 and August 2019. Most data were collected by phone interviews with living donors according to phone numbers provided to Directorate of the Jordanian Centre for Organ Transplantation; however, when possible, personal interviews were conducted. Donors were asked about their experiences during the periods before and after the donation process, including their feelings, emotions, and motives. Interviews were analyzed using the thematic analysis approach.

Results

Although 400 donors have been registered in our database, only 360 donors could be contacted. In the 360 participants who completed the interview, 337 were living kidney donors and 23 were living liver donors; 290 were Jordanians and 70 were non-Jordanians. Feelings were categorized into 2 main periods: before donation and after donation. Motives were analyzed as a separate entity.

Predonation period

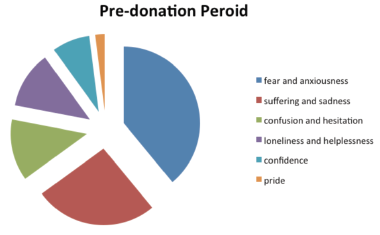

In the predonation period, most donors had experienced negative feelings. These

feelings included fear and anxiousness (39%), suffering and sadness (26%),

confusion and hesitation (13%), and loneliness and helplessness (12%). However,

donors also experienced positive feelings, such as confidence (8%) and pride

(2%) (Figure 1).

Fear and anxiousness predonation

Similar to other surgeries, the transplant journey can involve fear and anxiety

for donors. Many expressed that these were due to feelings related to the

success of the procedure and the positive recovery of the donor and the

recipient; others expressed that these feelings were due to the possible

complications. Nevertheless, most agreed that these feelings had disappeared

after the procedure, especially when the results were satisfactory.3-5

Some examples from interviews that described anxiousness and fear included the following: “Personally, I had experienced fear and anxiety due to the donation process, especially when I had discussed it with doctors; however, it was for a while”; “I was extremely afraid and anxious to go through life alone if I lost my brother”; and “I was always worried about him dying, but after I decided to donate, I feel proud of that.”

Suffering and sadness predonation

In Jordan, social relationships have significant effects on a patient’s life.

Therefore, many expressed how much they also suffered with regard to their

related recipient’s condition and the pain that the recipient endured. A lack of

social support and quality of life in recipients before transplant were the most

prevalent causes contributing to sadness in donors.6-8

Some examples from interviews that described suffering and sadness included the following: “I was sad about the life she lived; after donation, I can realize that she lives a new one”; “I had not got any support from the family, but I had proceeded with that in order to relieve my sister's suffering”; “My brother was kept on hemodialysis for 4 months and then I decided to donate; our life was suffering”; “I was witnessing her death in front of me; I support everyone who wants to donate”; and “It was very hard for me to see one of my children suffering from this disease (renal failure); however, it (the donation) was an easy procedure and I am doing well now.”

Confusion and hesitation predonation

Challenges with regard to decision making in donors were described as the

greatest challenge ever experienced during their lives. Being a donor has its

cons and pros, having both the risk of the procedure and the chance to enhance

the recipient’s life.9-12 Many donors reported that confusion had

subsided after sufficient explanation of the procedure, outcomes, and possible

complications.

Some examples from interviews that described confusion and hesitation included the following: “Before the donation, I was confused, but this is our destiny. Although my creatinine levels have been increased, I have no regret. If I could not help my brother, who will?”

Another participant stated, “I was confused and hesitated, but it occurred and successfully. I was scared about donation failure, as I will lose and she will not take any benefits.” Finally, “At the beginning, I was confused, but what can I do? He is my husband and I have to stand by him, or he will feel abandoned and lonely.”

Loneliness and helplessness predonation

Many donors have described the period before donation as one that lacked the

expected support from family and society. Therefore, the sense of being lonely

becomes evident during the decision-making process before donation; attending

hospital visits, lack of acknowledgement, and thinking about their worries

contributed to these feelings.13-16

Some examples from interviews that described feelings of loneliness and helplessness included the following: “I am very happy and proud to donate to my son. But I have complained of people’s views about donation; they said, ‘Why did you donate? There was no other to do this?’” Another donor stated, “I did not get any motivation or support from the family or anybody else. However, I have proceeded with this step. I do support donation, although we had faced intense objections from the uncles and aunts.” Also stated was the following: “I had no support from the surroundings, but I had moved forward to end the suffering that my sister faced.”

Confidence and pride predonation

Many donors are true heroes from the first day of the donation process or even

earlier. In addition to having a brave personality, many factors have encouraged

their strength to arise and their ability to make such an important decision. A

comprehensive understanding of the donation process, adequate discussions with

the treatment team, and having social support all contributed to minimizing the

hesitation that the donor or potential donor could encounter.9,17-19

Some examples from interviews that described confidence and pride included the following: “At the beginning, my mother was the potential donor but I insisted to be. I was so happy to donate and it should occur without any hesitation to enhance his life (her brother).”

Another stated, “I had asked my sisters to be the donor. After I had a sufficient discussion and evaluation with the transplant team, I had decided to donate without hesitation.” Another donor stated, “I was proud to donate, and I insisted to do that. I’ve understood the humanity meanings and I’ve felt my life was gifted. After everything has been cleared, I do support donation.” Finally, another stated, “I did not hesitate for a second, but I was worried a little bit, which had cleared after I got adequate support. I am very happy now, and he (her brother) is fine.”

Postdonation period

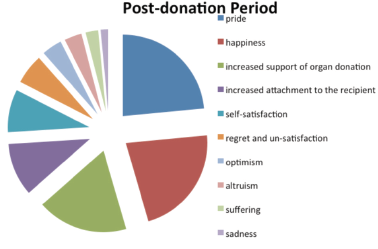

Unlike the period before donation, after donation, most donors described

positive emotional states marked with pride (23.5%), happiness (22%), increased

support of organ donation (18%), increased attachment to the recipient (10.5%),

and self-satisfaction (8.5%). Some, however, expressed their regret and

dissatisfaction (6%). The remaining (11.5%) had different emotions, such as

optimism (4%), altruism (3.5%), suffering (2.5%), and sadness (1.5%) (Figure 2).

Most donors stated that negative feelings were related to the unexpected outcomes of the donation procedure. Unsatisfactory results ranged from unwanted complications to the donor or recipient, failure of the transplant, or death in some cases. All of these factors significantly contribute to unfavorable experiences; therefore, known psychosocial risks after surgery must be cleared during the education process in an attempt to avoid problems afterward.6,8,10,20-24

It is worth mentioning that negative feelings were also observed in donors after favorable clinical results. Donors expressed that these were due to inadequate appreciation, lack of governmental support, and insufficient predonation educational counseling. Ongoing concerns remain that donors are at risk of negative psychosocial sequelae and that these outcomes deserve increased attention.25-29

These negative feelings after donation were displayed in the following examples from interviews: “Although my sister is dead, it was a charity. At least, she was happy when I decided to do that.” Another stated, “He is my son and I should stand by him; he does not have anyone but me. He has suffered and I am responsible for him. After 1 day after surgery, the transplant failed. In my opinion, if he stayed without a transplant, it would be better for him.” Other donors stated, “Psychologically, I am exhausted; especially, after Abdurrahman’s death” and “Thanks to god, my condition is getting better. However, I am sad about my brother’s death and upset as we had not been informed about all possibilities.” Another donor stated, “I am completely satisfied about the surgery, but I have gained some weight.” Further negative statements included, “Recently, I have developed kidney function impairment. I am complaining that to God. It was a medical mistake; my brother died, too” and “My husband does not appreciate what I have given. Although he is completely well now, but I do not know why he is treating me like that?” One donor stated, “I have developed kidney failure; I am regretting to donate.”

Pride and happiness postdonation

Certainly, the benefits of a state of accomplishment will not only impact the

donor’s condition and recovery but the entire procedure. Witnessing improvements

in a recipient’s quality of life and resolution of the effects of disease can

have remarkable effects on the donor’s pride and sense of happiness. Many donors

stated that their self-confidence and self-esteem increased after donation;

furthermore, being acknowledged and appreciated gave them the desire to have

that experience again.8,13-15,30-33

There are a number of examples in which pride and happiness were described during interviews: “It was the hardest situation I have ever experienced. She is my mother and she has sacrificed a lot for us. I will never retreat or hesitate in donation; if it was possible to do it again, I will.” Another stated, “I feel proud to do that. If I was not the donor, I will feel guilty if anything went wrong with him (her brother).” Another donor expressed, “I feel happy as my father has not been hospitalized or had hemodialysis again. Thanks to God, I am well recovered and I do not have any symptoms.” Other statements included, “I was scared about him dying; therefore, I decided to donate. I feel proud to do that”; “Her (his daughter) suffering should end, and I am happy for her”; and “It was a tough period but beautiful at the same time, and it was the best decision I have made in my entire life.” Another donor expressed the following: “It was a choice to die or live, I am proud to donate. However, if I have been asked ‘are you satisfied to donate’? I will say that I had felt that something was taken from my body, but at the end I am proud and I felt a soul was given.”

Increased support of organ donation postdonation

Donation is a unique life experience that has a special effect on a donor’s

attitude and reevaluation of life. After this opportunity, especially when it

proceeds with hopeful results, many donors have expressed it ends with the

rebirth of a new one. Increased support of organ donation is shown after an

ideal journey with donation (that is, good results for the donor and recipient).

Accordingly, having such donors spread awareness and enhance the social ideas

about donation, that is, promoting emotional support to potential donors and

including such donors in educational counseling, would be beneficial.7,10,34

Some examples from interviews that have described increased support of donation include the following: “If I didn’t donate, my mother or another family member would’ve done it; thanks to God the transplantation was successful and I encourage organ donation.” Another stated, “Charity should not be requested. I’m extremely happy and I encourage donation so everyone could have perfect health.” Another donor stated, “I’m in perfect condition and thank God I’m satisfied with my donation. I encourage donating so everybody is safe and in perfect health.” Another donor expressed the following: “I insisted to donate, and I’m very proud that I have donated. I am proud and I have learned the true meaning of humanity. I realized that a life was given to him! I do support donation.” Other statements were “It is the least I can do! It was very hard for me to give up on him. I encourage donation; if I had the chance I will give him my life” and “My brother was the most important thing in my life; I was the first who initiated donation.”

Increased attachment to recipient postdonation

The distinct donor-recipient relationship that emerges after transplant is

characterized in several ways. There is strengthened sense of responsibility

from the donor toward the recipient; in addition, many described that a soul or

a piece of their soul had been gifted. Interestingly, donors were thankful to

have that opportunity to help a loved one, and many family members have competed

for the chance to be the donor.

Donors expressed that family bonding had improved and become more solid. Moreover, in cases of the donor being a spouse, donors expressed increased love and kindness in their life.10,11,21,35-37

Some examples from interviews that described increased attachment to the recipient included the following: “After the transplantation had finished, I became responsible for him and the love has increased”; “My concern is my wife’s well-being; she is my and our children’s everything”; and “The family is the most important thing in the whole life. Wherever, we should be one attached family.” Another donor stated, “I am responsible for him, even in tiny details. We are together in every life event. Because of family bonding and morals that we have, I have to donate to my husband.” Another expressed, “The father is priceless; thanks to God I was willing to donate. I am responsible for him in everything right now.”

Self-satisfaction postdonation

It is important to note that self-satisfaction was a postdonation feeling that

did not completely adhere to enhancement of the recipient’s life. Even in cases

when transplant failed by either graft rejection or recipient death, donors

returned satisfaction to “What could be done had been done.” Nevertheless,

although observing improved health in the recipient can add further to the

feeling of self-satisfaction, the impact of a gifted organ on the recipient’s

psychological state will also promote it.21,33,38

Some examples from interviews that described self-satisfaction after donation included the following: “We are satisfied that we donated, and we did what we could. Anyhow, he is dead now, and if his death happened while we did not donate, we will blame ourselves through life.” Another donor stated, “I am doing well, and thanks to God I have self-satisfaction about what I have done. I do support donation in order to save lives.” A third donor expressed, “Thanks to God, I am psychologically well and self-satisfied that I did this charity; it is a part of me.”

Motives for donation

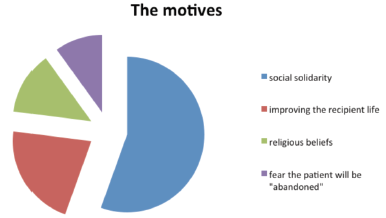

Most donors were motivated by social solidarity (55.5%) and improving the

recipient’s life (21.5%). Others invoked the role of their religious beliefs as

the main motive (13%), whereas some (10%) attributed their motive to fear that

patients will be “abandoned” (Figure 3).

Social solidarity motive

Social solidarity was the most common motive described by donors. In Jordan, as

in the rest of the Middle East region, the sturdy social relationship between

donors and recipients and between donors and other family members can ease the

decision-making process. In the interviews, many donors reported a strong

attachment to their loved one that had resulted directly from donation, and the

recipient that they donated to was the most precious gift that they had.39-41

Some examples from interviews that described social solidarity included the following: “My brother is the most precious thing I have, and I should donate to him without hesitation. Definitely, life gets better after the transplantation and his health has improved.” Others stated, “Nothing measures like the father” and “My brother is the most important part of my life. Actually, I am the one who initiated the donation.” Another stated, “Thanks to God for the blessing of transplantation. No one can realize how you feel when you experience your mother suffering.”

Motive to improving the recipient’s life

Witnessing a recipient with disease distress before transplant can spur the

desire to seek better life conditions for that person. Difficulties experienced

by recipients during hemodialysis or due to complications of liver and kidney

failure are accompanied by family members truly realizing the struggles in

transplant patients. Looking for an ultimate and definitive solution can become

the target for potential donors.42-44

Some examples from interviews that described improving the recipient’s life included the following: “She is my daughter and still young; thus, I shall donate to her to get better health”; “My full concern was to transplant a kidney and he gets his life back”; and “I did not get any motivation from the family and no one has supported me. However, I proceeded with that in order to demolish my sister’s suffering.”

Religious beliefs as a motive for donation

Religious beliefs have significant effects on the Jordanian society. Various

ways of charity have been encouraged in Islam. Even a “smile in front of your

brother” is considered to be a charity. Many donors described that the main

motive for their donation was simply charity and not for any gain.45 It was

emphasized by the Jordanian General Iftaa' Department to encourage organ

donation, to motivate society toward donating, and to regulate the process of

donation with specific instructions. “Organ donation is among the recommended

charitable deeds so long as the conditions of Sharia stipulated in this regard

are met. This is because it saves patients’ lives and relieves their pains.

Allah, The Almighty, says in this regard (what means), ‘and if any one saved a

life, it would be as if he saved the life of the whole people’” (Al-Mai`dah/32;

Resolution No. 215 [5/2015], dated 21/Ramadan/1436 AH, corresponding to 8/7/2015

AD, issued by the Board of Iftaa').

Some examples from interviews that described religious beliefs included the following: “Thanks to God it is all about the charity”; “The donation is a charitable deeds, as there is no harm on life”; and “Although my sister died, it is considered as a charity. At least, she was happy when I decided to donate.”

Fear that the patient will be “abandoned” as a motive

A sense that the recipient could be abandoned worried many donors in our

study.46,47 Being able to avoid such unfavorable feelings prompted some to

donate.

Some examples from interviews that described fear that the patient will be abandoned included the following: “This responsibility and it was hard for me to see her lonely and abandoned. I do support donation, and if I could gift my life, I will.” One participant stated, “Although the graft had been rejected, I am not regretting. Most important, she realized that she was not abandoned.” Another participant expressed the following: “The mother is a great person. It was not acceptable for me to abandon her; if she needs psychological and health support, I will give her every advice she needs.” Another stated, “I was beside her throughout her disease until she became a recipient. It was impossible for me to abandon her.”

Conclusions

The emotional suffering of living donors during the predonation period emphasizes the need for educational, social, and psychological support in addition to medical evaluations. Donors who had positive experiences after donation can play a role in educating and advocating for living-donor transplant. Finally, in Jordan, the social solidarity and religious beliefs are the most important factors that motivate donation.

References:

- Horvat LD, Shariff SZ, Garg AX, Donor Nephrectomy Outcomes Research N. Global trends in the rates of living kidney donation. Kidney Int. 2009;75(10):1088-1098.

CrossRef - PubMed - Hsieh CY, Chien CH, Liu KL, Wang HH, Lin KJ, Chiang YJ. Positive and negative effects in living kidney donors. Transplant Proc. 2017;49(9):2036-2039.

CrossRef - PubMed - Bozkurt O, Uyar M, Demir UF. Determination of health anxiety level in living organ donation. Transplant Proc. 2019;51(4):1139-1142.

CrossRef - PubMed - Agerskov H, Thiesson H, Specht K, B DP. Parents' experiences of donation to their child before kidney transplantation: A qualitative study. J Clin Nurs. 2019;28(9-10):1482-1490.

CrossRef - PubMed - Holscher CM, Leanza J, Thomas AG, et al. Anxiety, depression, and regret of donation in living kidney donors. BMC Nephrol. 2018;19(1):218.

CrossRef - PubMed - Jacobs CL, Gross CR, Messersmith EE, et al. Emotional and financial experiences of kidney donors over the past 50 years: The RELIVE Study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(12):2221-2231.

CrossRef - PubMed - Haljamae U, Nyberg G, Sjostrom B. Remaining experiences of living kidney donors more than 3 yr after early recipient graft loss. Clin Transplant. 2003;17(6):503-510.

CrossRef - PubMed - de Oliveira-Cardoso EA, dos Santos MA, Mastropietro AP, Voltarelli JC. Bone marrow donation from the perspective of sibling donors. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2010;18(5):911-918.

CrossRef - PubMed - Waterman AD, Covelli T, Caisley L, et al. Potential living kidney donors' health education use and comfort with donation. Prog Transplant. 2004;14(3):233-240.

CrossRef - PubMed - Pradel FG, Mullins CD, Bartlett ST. Exploring donors' and recipients' attitudes about living donor kidney transplantation. Prog Transplant. 2003;13(3):203-210.

CrossRef - PubMed - Gill P, Lowes L. Gift exchange and organ donation: donor and recipient experiences of live related kidney transplantation. Int J Nurs Stud. 2008;45(11):1607-1617.

CrossRef - PubMed - Hanson CS, Chadban SJ, Chapman JR, et al. The expectations and attitudes of patients with chronic kidney disease toward living kidney donor transplantation: a thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. Transplantation. 2015;99(3):540-554.

CrossRef - PubMed - Kisch AM, Forsberg A, Fridh I, et al. The meaning of being a living kidney, liver, or stem cell donor-a meta-ethnography. Transplantation. 2018;102(5):744-756.

CrossRef - PubMed - Adams-Leander S. The experiences of African-American living kidney donors. Nephrol Nurs J. 2011;38(6):499-508; quiz 509.

CrossRef - PubMed - Holroyd E, Molassiotis A. Hong Kong Chinese perceptions of the experience of unrelated bone marrow donation. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51(1):29-40.

CrossRef - PubMed - Taylor LA, McMullen P. Living kidney organ donation: experiences of spousal support of donors. J Clin Nurs. 2008;17(2):232-241.

CrossRef - PubMed - Waterman AD, Barrett AC, Stanley SL. Optimal transplant education for recipients to increase pursuit of living donation. Prog Transplant. 2008;18(1):55-62.

CrossRef - PubMed - Hart A, Bruin M, Chu S, Matas A, Partin MR, Israni AK. Decision support needs of kidney transplant candidates regarding the deceased donor waiting list: A qualitative study and conceptual framework. Clin Transplant. 2019;33(5):e13530.

CrossRef - PubMed - Burroughs TE, Waterman AD, Hong BA. One organ donation, three perspectives: experiences of donors, recipients, and third parties with living kidney donation. Prog Transplant. 2003;13(2):142-150.

CrossRef - PubMed - Kang da HS, Yang J. [Adaptation Experience of Living Kidney Donors after Donation]. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2016;46(2):271-282.

CrossRef - PubMed - Ruck JM, Van Pilsum Rasmussen SE, Henderson ML, Massie AB, Segev DL. Interviews of living kidney donors to assess donation-related concerns and information-gathering practices. BMC Nephrol. 2018;19(1):130.

CrossRef - PubMed - AlBugami MM, AlOtaibe FE, Boqari D, AlAbadi AM, Hamawi K, Bel'eed-Akkari K. Why potential living kidney donors do not proceed for donation: a single-center experience. Transplant Proc. 2019;51(2):504-508.

CrossRef - PubMed - Weng LC, Huang HL, Wang YW, Chang CL, Tsai CH, Lee WC. The coping experience of Taiwanese male donors in living donor liver transplantation. Nurs Res. 2012;61(2):133-139.

CrossRef - PubMed - Lentine KL, Lam NN, Segev DL. Risks of living kidney donation: current state of knowledge on outcomes important to donors. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;14(4):597-608.

CrossRef - PubMed - Sener A, Cooper M. Live donor nephrectomy for kidney transplantation. Nat Clin Pract Urol. 2008;5(4):203-210.

CrossRef - PubMed

- Dew MA, Jacobs CL, Jowsey SG, et al. Guidelines for the psychosocial evaluation of living unrelated kidney donors in the United States. Am J Transplant. 2007;7(5):1047-1054.

CrossRef - PubMed - Jowsey SG, Schneekloth TD. Psychosocial factors in living organ donation: clinical and ethical challenges. Transplant Rev (Orlando). 2008;22(3):192-195.

CrossRef - PubMed - Olbrisch ME, Benedict SM, Haller DL, Levenson JL. Psychosocial assessment of living organ donors: clinical and ethical considerations. Prog Transplant. 2001;11(1):40-49.

CrossRef - PubMed - Schroder NM, McDonald LA, Etringer G, Snyders M. Consideration of psychosocial factors in the evaluation of living donors. Prog Transplant. 2008;18(1):41-48; quiz 49.

CrossRef - PubMed - Kim HS, Yoo YS, Lee MD, Kim JI. Experiences of living donors for small bowel transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2017;49(5):1138-1141.

CrossRef - PubMed - Meyer KB, Bjork IT, Wahl AK, Lennerling A, Andersen MH. Long-term experiences of Norwegian live kidney donors: qualitative in-depth interviews. BMJ Open. 2017;7(2):e014072.

CrossRef - PubMed - Schover LR, Streem SB, Boparai N, Duriak K, Novick AC. The psychosocial impact of donating a kidney: long-term follow-up from a urology based center. J Urol. 1997;157(5):1596-1601.

CrossRef - PubMed - Christopher KA. The experience of donating bone marrow to a relative. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2000;27(4):693-700.

CrossRef - PubMed - Goldaracena N, Jung J, Aravinthan AD, et al. Donor outcomes in anonymous live liver donation. J Hepatol. 2019;71(5):951-959.

CrossRef - PubMed - Wanner M, Bochert S, Schreyer IM, Rall G, Rutt C, Schmidt AH. Losing the genetic twin: donor grief after unsuccessful unrelated stem cell transplantation. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:2.

CrossRef - PubMed - Andersen MH, Mathisen L, Oyen O, Wahl AK, Hanestad BR, Fosse E. Living donors' experiences 1 wk after donating a kidney. Clin Transplant. 2005;19(1):90-96.

CrossRef - PubMed - Pulewka K, Wolff D, Herzberg PY, et al. Physical and psychosocial aspects of adolescent and young adults after allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation: results from a prospective multicenter trial. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2017;143(8):1613-1619.

CrossRef - PubMed - Switzer GE, Dew MA, Magistro CA, et al. The effects of bereavement on adult sibling bone marrow donors' psychological well-being and reactions to donation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1998;21(2):181-188.

CrossRef - PubMed - DiMartini A, Cruz RJ, Jr., Dew MA, et al. Motives and decision making of potential living liver donors: comparisons between gender, relationships and ambivalence. Am J Transplant. 2012;12(1):136-151.

CrossRef - PubMed - Zhao WY, Zeng L, Zhu YH, et al. Psychosocial evaluation of Chinese living related kidney donors. Clin Transplant. 2010;24(6):766-771.

CrossRef - PubMed - Lennerling A, Forsberg A, Nyberg G. Becoming a living kidney donor. Transplantation. 2003;76(8):1243-1247.

CrossRef - PubMed - Garcia Martinez M, Valentin Munoz MO, Ormeno Gomez M, Martinez Alpuente I, Dominguez-Gil Gonzalez B. Can we improve the effectiveness of the Spanish nondirected donation program? Transplant Proc. 2019;51(9):3030-3033.

CrossRef - PubMed

- Heru A. Should narrative coherence be considered in the assessment of motivation in the non-directed kidney donation? Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2018;55:1-3.

CrossRef - PubMed - Klinkenberg EF, Huis In 't Veld EMJ, de Wit PD, de Kort W, Fransen MP. Barriers and motivators of Ghanaian and African-Surinamese migrants to donate blood. Health Soc Care Community. 2019;27(3):748-756.

CrossRef - PubMed - Maghen A, Vargas GB, Connor SE, et al. Spirituality and religiosity of non-directed (altruistic) living kidney donors. J Clin Nurs. 2018;27(7-8):1662-1672.

CrossRef - PubMed - Wadström J, von Zur-Mühlen B, Lennerling A, Westman K, Wennberg L, Fehrman Ekholm I. Living anonymous renal donors do not regret: intermediate and long-term follow-up with a focus on motives and psychosocial outcomes. Ann Transplant. 2019;24:234–241.

CrossRef - PubMed - Balliet W, Kazley AS, Johnson E, et al. The non-directed living kidney donor: Why donate to strangers? J Ren Care. 2019;45(2):102-110.

CrossRef - PubMed

Volume : 18

Issue : 1

Pages : 22 - 28

DOI : 10.6002/ect.TOND-TDTD2019.L25

From the 1Jordanian Ministry of Health, Jordanian Centre of Organ

Transplantation, General and HPB Surgery, the 2Jordanian Ministry of

Health, General Surgery, and the 3Faculty of Medicine, The University

of Jordan, Amman, Jordan

Acknowledgements: The authors have no sources of funding for this study

and have no conflicts of interest to declare. We thank Lubna Mohammed Abusalemeh

and Dua'a Mohammed D'amas (both from the Directorate of the Jordanian Centre for

Organ Transplantation) for assistance with interviews and data collection.

Corresponding author: Abdel-Hadi Al Breizat, Kingdom of Jordan

–Amman-Khalda- Mahmoud Adwan St., Building No. 17, Apartment 17, PO Box 293,

Amman, 11821 Jordan

Phone: +962 795575077

E-mail:

dr.hadibriezat@gmail.com

Figure 1. Distribution of Different Feelings Before Donation Among Living Donors

Figure 2. Distribution of Different Feelings After Donation Among Living Donors

Figure 3. Distribution of Different Motives That Contributed to Donation