Volume: 20 Issue: 3 March 2022

FULL TEXT

Abstract

Management of benign liver tumors represents still an open debate, with no clear guidelines for patient selection, treatment options, and indications to surgical intervention. Usually, most of these diseases are conservatively treated, in view of their low potential malignancy and incidental diagnosis. However, when the lesions are symptomatic, with a major hepatic parenchyma involvement or life-threatening complications, liver transplant represents the only curative option. The scope of this review is to present an up-to-date state of the art of transplantable benign hepatic neoplasms.

Key words : Hepatic neoplasms, Polycystic liver disease, Transplantation

Introduction

The widespread use of imaging tests, mostly ultrasonography, has led to an increase in the detection of benign liver solid tumors.1 In the United States, the reported incidence is approximately 20%, exceeding the number of malignant tumors by a

2-to-1 ratio.2 Most of these benign lesions generally remain asymptomatic over the course of the years; however, they may cause pressure on adjacent structures, leading to abdominal pain, discomfort, and early satiety. Other described symptoms include fever, jaundice, dyspnea, high-output cardiac failure, and hemobilia, with possible compression of the vena cava and/or biliary structures.3

A surgical approach for benign liver lesions accounts for 5% to 10% of patients, with surgery mainly involving either enucleation or resection, due to a better knowledge of liver anatomy, refinements in surgical techniques and minimally invasive surgery, and enhanced postoperative care. As a consequence, today, an increasing number of patients with benign lesions are considered for surgical treatment.4

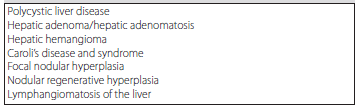

Rarely, benign lesions require orthotopic liver transplant (OLT), as in the case of giant dimension lesions or complete replacement of the hepatic parenchyma. Other indications for OLT include preneoplastic lesions with high risk of malignant transformation, those that have associations with metabolic diseases, and cases of rupture or increased risk of life-threatening complications. A list of the most common benign hepatic tumors treatable with liver transplant is presented in Table 1.

The aim of the present review is to provide the state of the art of indications and long-term results for OLT in cases of benign hepatic lesions, where, in addition to organ donor shortages, there is also the ethical dilemma in which symptom burden is weighed against the risks of long-term immuno-suppression and a complex surgical procedure.

Polycystic Liver Disease

Polycystic liver disease (PLD) is a rare condition in which the hepatic parenchyma is replaced by fluid-filled cysts. Polycystic liver disease is most common in people affected by autosomal dominant adult polycystic kidney disease. The prevalent cause is inheritance, following mutations in 2 distinct genes (PKD1 and PKD2), but PLD can also occur randomly. In these cases, PLD is usually associated with alterations in the SEC63 and PRKCXH genes, which code for special proteins involved in protein processing. Once mutated, these proteins affect PKD1 and PKD2, which will lead to the formation of cysts.5 Cyst hemorrhage and infection are generally self-limiting with adequate medical therapy, although severe sepsis and fatal bleeding have been described.6

As hepatic cysts grow, they cause a mass effect and exert pressure on adjacent organs, often becoming clinically symptomatic with age and advanced renal disease. Other risk factors associated with severe cystic disease include female sex, exogenous female hormones, and multiple pregnancies; thus, the natural disease course is more predominant in women, with a transplant ratio of 5.7:1 compared with that shown in male patients.7

In patients with PLD, there are some alternative therapies that can be tried before proceeding with OLT. Somatostatin, a natural occurring hormone in the gastrointestinal tract, decreases ?uid secretion and proliferation. Despite the short-acting half-life of naturally occurring somatostatin, synthetic long-acting somatostatins have been developed, which have shown excellent results in patients with PLD.8

In patients with symptoms caused by 1 dominant cyst (generally >5 cm in diameter), radiological intervention aimed at reducing cyst volume by puncturing is a feasible option. The remnant of the cyst is injected with a sclerosing agent to prevent future growth through the destruction of the inner epithelial lining.9

In addition to the above nonsurgical therapies, another treatment option for symptom relief is surgical defenestration, generally performed laparoscopically,10 and eventually surgical resection, with preservation of liver volume. However, potential risks from the surgical procedure related to benign pathology can still occur, varying from biliary leak to massive ascites. These options should be carefully counterbalanced in highly selected patients for which immunosuppressive risk might result in a higher burden.

Orthotopic liver transplant represents the only curative treatment for PLD. Once listed, patients with PLD are generally awarded exception Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) points every 3 months,11 as native MELD scores tend to be low. Survival rates are excellent compared with liver transplant for other indications. According to the European liver transplant registry, the 1-year, 5-year, and 10-year patient survival rates are 89%, 85%, and 77%, respectively.12

Liver Cell Adenoma/Adenomatosis

Hepatic adenoma is due to an abnormal proliferation of hepatic cells. Diagnosis of this condition has increased after prescription of oral contraceptives became widespread. Thus, hepatic adenomas are more common in female compared with male patients (ratio of 10:1).13

The reported prevalence is 3 cases per 100 000 individuals, predominantly in individuals below 40 years of age. Additionally, hepatic adenomas have been described in association with genetic conditions, such as glycogen storage diseases, hepatic vascular disease, McCune-Albright disease, and an HNF1a germ-line mutation with maturity-onset diabetes of the young type 3 (MODY3).14-16

One of the major complications, which occurs in up to 42% of patients, is spontaneous bleeding17; it is often accompanied by right upper quadrant pain, along with a sense of early satiety and is especially present when the lesion is larger than 5 cm in diameter. Although the hemorrhage can be stopped, it remains a major complication for which the risks are not well defined.18

Another serious complication is the risk of malignant transformation, estimated in 3% of the cases.15 When more than 10 adenomas are present, the condition is named liver adenomatosis. In view of the described risks, patients with liver adenomatosis should have a specific follow-up annually, with specific imaging (usually magnetic resonance) and biological tests, as malignancy potentiality does not disappear even in the case of regression of the adenoma after oral contraceptive discontinuation.14

The management of liver adenomatosis remains problematic. Surgical resection is widely practiced for lesions that remain >5 cm after suspension of oral contraceptives for 6 months or lesions with malignant characteristics on imaging. Resection is also recommended for male patients, given the dispro-portionately high number of b-catenin mutations and the signi?cant risk of malignant transformation. Transarterial embolization represents an effective alternative treatment to surgery in an elective scenario.19

Orthotopic liver transplant is rarely performed for patients with hepatic adenoma (solitary giant) or liver adenomatosis.20 With the current availability of alternative treatments, we recommend that OLT be considered as the last therapeutic option for patients with symptomatic and multiple growing adenomas and when there is a history of repeated complications or partial resection of larger lesions, with increased serum α-fetoprotein level or concern about malignant transformation.21

Hepatic Hemangioma

Hepatic hemangioma (HH) is a common benign liver disease. This neoplasm is formed by clusters of blood-filled cavities, which are lined by endothelial cells and fed by the hepatic artery. Most HHs are asymptomatic; diagnosis occurs incidentally after imaging tests, with very low malignant potential.22 Often, a differential diagnosis with other liver lesions could be easily made via ultrasonographic imaging: the absence of blood flow differentiates HH from hepatocellular carcinoma, and it is generally surrounded by intra- or peritumoral vascularity. In hypoechoic lesions, a peripheral echogenic rim can instead suggest HH. Conversely, a peripheral perilesional hypoechoic rim, commonly called the “target sign,” is infrequently detected in HH. Another possible differential diagnosis is with focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH), which has the characteristic “spoke-wheel sign.” Caution should be maintained when assessing the fatty liver, in which a typical hemangioma could appear hypoechoic compared with the intense hyperechoic liver parenchyma.1

Typical HHs consist of capillary hemangiomas. Their dimensions range from a few mm to 3 cm, and they tend to remain stable over the course of the years. Small (few mm to 3 cm) and medium (3-10 cm) HHs are rounded lesions that do not require intervention and only require regular follow-up and monitoring. If the dimension reaches >10 or >20 cm, these “cavernous” or “giant” lesions usually develop symptoms and complications, prompting the need for treatment.23

Surgical referral of HH cases is recommended for patients with Kasabach-Merritt syndrome,24 a disorder characterized by thrombocytopenia, coagulopathy, and microangiopathic hemolytic anemia; surgery is also recommended for those with growing lesions or symptomatic lesions.3 When pressure on adjacent organs and vessels exists, which may result in severe pain, symptoms such as Budd-Chiari syndrome, jaundice, and lower extremity edema are often present.

For cavernous HH, the evolution is unpredictable and often unfavorable, with serious complications requiring particular surgical expertise. Spontaneous or trauma-induced bleeding from the neoplasm is a rare but potentially fatal complication of HH that needs emergency laparotomy.25

According to existing data, there is no known pharmacological therapy able to reduce the size of HH. Antiangiogenic therapy with bevacizumab (a monoclonal antibody capable of inhibiting endothelial growth factor activity) has been utilized, but further studies are needed.26

There is no consensus regarding the optimal management of giant HH.27 Although less invasive techniques, such as transarterial embolization of the feeding artery and radiofrequency ablation, could induce reduction of the size of giant HH, there is also evidence that surgical management is helpful for symptom relief and has low risk of mortality.28

Orthotopic liver transplant represents an alterna-tive treatment option in selected cases, with excellent outcomes in terms of safety and survival.29 Given the low numbers of cases reported in the literature, it can be concluded that OLT in this setting constitutes an extremely rare indication. Nonetheless, transplant should be considered for patients with unresectable HH or life-threatening conditions.

Caroli Disease and Caroli syndrome

Caroli disease (CD) is a rare congenital disorder characterized by cystic dilatation of the intrahepatic biliary ducts. The common etiology of this fibrocystic disease is probably related to ductal plate malformation at different levels of the intrahepatic biliary tree. Two forms have been identified. The first has a focal distribution and thus is identified as “simple Caroli disease” and consists of abnormally dilated bile ducts affecting only an isolated portion of the liver.30 The second is more diffuse and, when associated with portal hypertension and hepatic fibrosis, is known as “Caroli syndrome” (CS).31 Caroli disease equally affects men and women; its prevalence is 1 in 1 000 000 people, with more reported cases of CS. An association with polycystic kidney disease is common.32

Although CD is present from birth, patients do not normally present with symptoms until early adulthood. According to the Todani classi?cation of choledochal cysts, CD is also known as choledochal cyst type V.33

The main clinical manifestation is dominated by recurring cholangitis, the frequency of which may vary from one patient to another but always requiring adequate and prompt treatment to manage septic complications. Chronic abdominal pain, pancreatitis, and liver abscess are other disease manifestations; cholangiocarcinoma can also complicate the untreated course of CD, with an overall reported incidence of 6.6%.34 In this setting, the diagnosis of cholan-giocarcinoma proves to be challenging, and no clear clinical or biochemical parameters are associated with an early diagnosis.

In asymptomatic patients with CD, a routine follow-up is therefore recommended to monitor biochemically liver function for liver failure progression, particularly in view of the underlying hepatic ?brosis, portal hypertension, or malignant transformation. Policies of other centers can be more aggressive, especially in symptomatic patients who have previously undergone medical treatment or where palliative therapy has failed, including drainage by radiological procedures for symptom relief.35

Surgical treatment with liver resection or OLT should be offered to patients with CS or CD at early stages to avoid recurrent sepsis and/or malignant transformation. Liver resection is the treatment of choice for patients with segmental forms (simple forms) and the absence of congenital hepatic fibrosis. It is not recommended as a bridge therapy to OLT.

Generally, liver failure does not represent the main condition leading to OLT in CD patients; therefore, the mere application of the MELD score fails to match with the possibility to proceed to transplant in patients with CD and CS. In cases of recurrent cholangitis, an exception to MELD score and the use of an upgrade of priority after a few months on the waiting list are envisaged.36 Although early postoperative outcomes after OLT include a high incidence of septic complications, the long-term survival is excellent (>80%).12,37

Other Rare Indications for Liver Transplant

This section lists other benign diseases for which OLT is rarely performed.

First is FNH, a nonmalignant hepatic neoplasm, not from a vascular origin, where biliary ducts are always present. Diagnosis is often incidental, following radiological imaging. Focal nodular hyperplasia generally remains asymptomatic and is diagnosed as an incidental clinical finding or following post-mortem studies. It represents about 8% of non-hemangiomatous lesions and 66% of all benign non-hemangiomatous lesions.38 The occurrence of FNH is mostly solitary (80% to 95%) and is usually <5 cm in diameter. As per other benign liver diseases, FNH has an association with the estrogenous hormones, with a female-to-male ratio of 9:1, independent of age.39 There are other names for FNH, including solitary hyperplastic nodule, hepatic hamartoma, focal cirrhosis, hamartomatous cholangiohepatoma, and hepatic pseudotumor.4 The approach to therapy should be conservative; in extensive asymptomatic cases, a biopsy to confirm the benign lesion and routine imaging follow-up should be preferred versus surgical resection. Orthotopic liver transplant is an indication mainly limited to uncertain malignancy potential or symptomatic unresectable lesions.18,40

Another benign disease is nodular regenerative hyperplasia (NRH), a rare hepatic disease charac-terized by the presence of multiple, small nonfibrotic nodules (<1 cm). Nodular regenerative hyperplasia is thought to be of vascular origin, with the potential to evolve in noncirrhotic portal hypertension,41 representing actually its main cause. It was ?rst described by Steiner42 and has an incidence of 2.5% in autoptic series and 4.4% in liver biopsies.43 The development of NRH has been associated with a variety of hematological disorders, including myelo- and lymphoproliferative diseases, autoimmune diseases, inflammatory and immunodeficiency conditions, and the use of immunosuppressive medications. Specifically, drugs associated with NRH include highly active antiretroviral therapies, platin-based chemotherapies, and thiopurines, particularly azathioprine and thioguanine.44 Treatment for NRH should involve the correction of the hypercoagulable state45 and should be focused on portal hypertensive complications (ie, beta-blockers, variceal ligation, and/or porto-systemic shunts). Orthotopic liver transplant must only be considered for patients with severe portal hypertension and/or liver failure, where excellent outcomes have been described.46

Finally, hepatic lymphangiomatosis represents another hepatic condition, accounting for 5% of OLTs for benign indications.47 It is characterized by abnor-mal lymphatic proliferation causing intrahepatic cystic or cavernous lesions in the liver, with the potential to grow to massive proportions, causing symptoms from compression and destruction of vital adjacent organs to organ failure.

Conclusions

Although liver transplant cannot be considered a first-line treatment for patients with a diagnosis of benign hepatic disease, it is the only therapeutic option in selected patients who are not amenable to resection, with refractory symptoms, or when malignant transformation cannot be ruled out. The overall survival rates at 1, 3, and 5 years are 90.9%, 85.2%, and 81.8%, respectively,47 with older age associated with worse outcomes. Alternative treatments, mainly representing only a palliative approach, are liver resection or radiological interventions, such as transarterial embolization of the feeding artery and radiofrequency ablation.

References:

- Kaltenbach TE, Engler P, Kratzer W, et al. Prevalence of benign focal liver lesions: ultrasound investigation of 45,319 hospital patients. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2016;41(1):25-32. doi:10.1007/s00261-015-0605-7

CrossRef - PubMed - Gibbs JF, Litwin AM, Kahlenberg MS. Contemporary management of benign liver tumors. Surg Clin North Am. 2004;84(2):463-480. doi:10.1016/j.suc.2003.11.003

CrossRef - PubMed - European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of benign liver tumours. J Hepatol. 2016;65(2):386-398. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2016.04.001

CrossRef - PubMed - Fodor M, Primavesi F, Braunwarth E, et al. Indications for liver surgery in benign tumours. Eur Surg. 2018;50(3):125-131. doi:10.1007/s10353-018-0536-y

CrossRef - PubMed - van Aerts RMM, van de Laarschot LFM, Banales JM, Drenth JPH. Clinical management of polycystic liver disease. J Hepatol. 2018;68(4):827-837. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2017.11.024

CrossRef - PubMed - Chandok N. Polycystic liver disease: a clinical review. Ann Hepatol. 2012;11(6):819-826.

CrossRef - PubMed - Alsager M, Neong SF, Gandhi R, et al. Liver transplantation in adult polycystic liver disease: the Ontario experience. BMC Gastroenterol. 2021;21(1):115. doi:10.1186/s12876-021-01703-x

CrossRef - PubMed - Gevers TJ, Drenth JP. Somatostatin analogues for treatment of polycystic liver disease. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2011;27(3):294-300. doi:10.1097/MOG.0b013e328343433f

CrossRef - PubMed - Wijnands TF, Gortjes AP, Gevers TJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of aspiration sclerotherapy of simple hepatic cysts: a systematic review. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2017;208(1):201-207. doi:10.2214/AJR.16.16130

CrossRef - PubMed - Wabitsch S, Kastner A, Haber PK, et al. Laparoscopic versus open liver resection for benign tumors and lesions: a case matched study with propensity score matching. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2019;29(12):1518-1525. doi:10.1089/lap.2019.0427

CrossRef - PubMed - Arrazola L, Moonka D, Gish RG, Everson GT. Model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) exception for polycystic liver disease. Liver Transpl. 2006;12(12 Suppl 3):S110-111. doi:10.1002/lt.20974

CrossRef - PubMed - Adam R, Karam V, Delvart V, et al. Evolution of indications and results of liver transplantation in Europe. A report from the European Liver Transplant Registry (ELTR). J Hepatol. 2012;57(3):675-688. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2012.04.015

CrossRef - PubMed - Barbier L, Nault JC, Dujardin F, et al. Natural history of liver adenomatosis: A long-term observational study. J Hepatol. 2019;71(6):1184-1192. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2019.08.004

CrossRef - PubMed - Krause K, Tanabe KK. A shifting paradigm in diagnosis and management of hepatic adenoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2020;27(9):3330-3338. doi:10.1245/s10434-020-08580-w

CrossRef - PubMed - Miller GC, Campbell CM, Manoharan B, et al. Subclassification of hepatocellular adenomas: practical considerations in the implementation of the Bordeaux criteria. Pathology. 2018;50(6):593-599. doi:10.1016/j.pathol.2018.05.003

CrossRef - PubMed - Sakellariou S, Al-Hussaini H, Scalori A, et al. Hepatocellular adenoma in glycogen storage disorder type I: a clinicopathological and molecular study. Histopathology. 2012;60(6B):E58-E65. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2559.2011.04153.x

CrossRef - PubMed - Bieze M, Phoa SS, Verheij J, van Lienden KP, van Gulik TM. Risk factors for bleeding in hepatocellular adenoma. Br J Surg. 2014;101(7):847-855. doi:10.1002/bjs.9493

CrossRef - PubMed - Marino IR, Scantlebury VP, Bronsther O, Iwatsuki S, Starzl TE. Total hepatectomy and liver transplant for hepatocellular adenomatosis and focal nodular hyperplasia. Transpl Int. 1992;5 Suppl 1:S201-S205. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-77423-2_64

CrossRef - PubMed - van Rosmalen BV, Coelen RJS, Bieze M, et al. Systematic review of transarterial embolization for hepatocellular adenomas. Br J Surg. 2017;104(7):823-835. doi:10.1002/bjs.10547

CrossRef - PubMed - Vennarecci G, Santoro R, Antonini M, et al. Liver transplantation for recurrent hepatic adenoma. World J Hepatol. 2013;5(3):145-148. doi:10.4254/wjh.v5.i3.145

CrossRef - PubMed - Ercolani G, Grazi GL, Pinna AD. Liver transplantation for benign hepatic tumors: a systematic review. Dig Surg. 2010;27(1):68-75. doi:10.1159/000268628

CrossRef - PubMed - Bajenaru N, Balaban V, Savulescu F, Campeanu I, Patrascu T. Hepatic hemangioma -review. J Med Life. 2015;8 Spec Issue:4-11.

CrossRef - PubMed - Eghlimi H, Arasteh P, Azade N. Orthotopic liver transplantation for management of a giant liver hemangioma: a case report and review of literature. BMC Surg. 2020;20(1):142. doi:10.1186/s12893-020-00801-z

CrossRef - PubMed - Ryan C, Price V, John P, et al. Kasabach-Merritt phenomenon: a single centre experience. Eur J Haematol. 2010;84(2):97-104. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0609.2009.01370.x

CrossRef - PubMed - Giuliante F, Ardito F, Vellone M, et al. Reappraisal of surgical indications and approach for liver hemangioma: single-center experience on 74 patients. Am J Surg. 2011;201(6):741-748. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2010.03.007

CrossRef - PubMed - Lee M, Choi JY, Lim JS, Park MS, Kim MJ, Kim H. Lack of anti-tumor activity by anti-VEGF treatments in hepatic hemangiomas. Angiogenesis. 2016;19(2):147-153. doi:10.1007/s10456-016-9494-9

CrossRef - PubMed - Colombo, M. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of benign liver tumors. Clin Liver Dis. 2020;15:133-135. doi:10.1002/cld.933

CrossRef - PubMed - Xie QS, Chen ZX, Zhao YJ, Gu H, Geng XP, Liu FB. Outcomes of surgery for giant hepatic hemangioma. BMC Surg. 2021;21(1):186. doi:10.1186/s12893-021-01185-4

CrossRef - PubMed - Prodromidou A, Machairas N, Garoufalia Z, et al. Liver transplantation for giant hepatic hemangioma: a systematic review. Transplant Proc. 2019;51(2):440-442. doi:10.1016/j.transproceed.2019.01.018

CrossRef - PubMed - Caroli J, Couinaud C, Soupault R, Porcher P, Eteve J. [A new disease, undoubtedly congenital, of the bile ducts: unilobar cystic dilation of the hepatic ducts]. Sem Hop. 1958;34(8/2):496-502/SP.

CrossRef - PubMed - Wu KL, Changchien CS, Kuo CM, Chuah SK, Chiu YC, Kuo CH. Caroli's disease - a report of two siblings. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;14(12):1397-1399. doi:10.1097/00042737-200212000-00019

CrossRef - PubMed - Summerfield JA, Nagafuchi Y, Sherlock S, Cadafalch J, Scheuer PJ. Hepatobiliary fibropolycystic diseases. A clinical and histological review of 51 patients. J Hepatol. 1986;2(2):141-156. doi:10.1016/s0168-8278(86)80073-3

CrossRef - PubMed - Todani T, Watanabe Y, Narusue M, Tabuchi K, Okajima K. Congenital bile duct cysts: Classification, operative procedures, and review of thirty-seven cases including cancer arising from choledochal cyst. Am J Surg. 1977;134(2):263-269. doi:10.1016/0002-9610(77)90359-2

CrossRef - PubMed - Fahrner R, Dennler SG, Inderbitzin D. Risk of malignancy in Caroli disease and syndrome: A systematic review. World J Gastroenterol. 2020;26(31):4718-4728. doi:10.3748/wjg.v26.i31.4718

CrossRef - PubMed - De Kerckhove L, De Meyer M, Verbaandert C, et al. The place of liver transplantation in Caroli's disease and syndrome. Transpl Int. 2006;19(5):381-388. doi:10.1111/j.1432-2277.2006.00292.x

CrossRef - PubMed - Harring TR, Nguyen NT, Liu H, Goss JA, O’Mahony CA. Caroli disease patients have excellent survival after liver transplant. J Surg Res. 2012;177(2):365-372. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2012.04.022

CrossRef - PubMed - Adam R, Karam V, Cailliez V, et al. 2018 Annual Report of the European Liver Transplant Registry (ELTR) - 50-year evolution of liver transplantation. Transpl Int. 2018;31(12):1293-1317. doi:10.1111/tri.13358

CrossRef - PubMed - Hsee LC, McCall JL, Koea JB. Focal nodular hyperplasia: what are the indications for resection? HPB (Oxford). 2005;7(4):298-302. doi:10.1080/13651820500273624

CrossRef - PubMed - Clouston AD, Hübscher SG. Transplantation pathology. In: Burt AD, Ferrell LD, Hübscher SG (eds.). Macsween's Pathology of the Liver. 7th ed. Elsevier; 2018:880-965.

CrossRef - PubMed - Ra SH, Kaplan JB, Lassman CR. Focal nodular hyperplasia after orthotopic liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2010;16(1):98-103. doi:10.1002/lt.21956

CrossRef - PubMed - Chawla Y, Dhiman RK. Intrahepatic portal venopathy and related disorders of the liver. Semin Liver Dis. 2008;28(3):270-281. doi:10.1055/s-0028-1085095

CrossRef - PubMed - Steiner PE. Nodular regenerative hyperplasia of the liver. Am J Pathol. 1959;35:943-953.

CrossRef - PubMed - Barge S, Grando V, Nault JC, et al. Prevalence and clinical significance of nodular regenerative hyperplasia in liver biopsies. Liver Int. 2016;36(7):1059-1066. doi:10.1111/liv.12974

CrossRef - PubMed - Hartleb M, Gutkowski K, Milkiewicz P. Nodular regenerative hyperplasia: evolving concepts on underdiagnosed cause of portal hypertension. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17(11):1400-1409. doi:10.3748/wjg.v17.i11.1400

CrossRef - PubMed - Bihl F, Janssens F, Boehlen F, Rubbia-Brandt L, Hadengue A, Spahr L. Anticoagulant therapy for nodular regenerative hyperplasia in a HIV-infected patient. BMC Gastroenterol. 2010;10:6. doi:10.1186/1471-230X-10-6

CrossRef - PubMed - Manzia TM, Gravante G, Di Paolo D, et al. Liver transplantation for the treatment of nodular regenerative hyperplasia. Dig Liver Dis. 2011;43(12):929-934. doi:10.1016/j.dld.2011.04.004

CrossRef - PubMed - Sundar Alagusundaramoorthy S, Vilchez V, Zanni A, et al. Role of transplantation in the treatment of benign solid tumors of the liver: a review of the United Network of Organ Sharing data set. JAMA Surg. 2015;150(4):337-342. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2014.3166

CrossRef - PubMed

Volume : 20

Issue : 3

Pages : 231 - 236

DOI : 10.6002/ect.2021.0447

From the 1Department of Surgical Sciences, Sapienza University, Rome, Italy; and the 2Department of Surgery, Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA

Acknowledgements: This manuscript was originally presented as part of the International Symposium on “Benign and Malignant Tumors in Liver With or Without Cirrhosis “ held in Ankara, Turkey on June 24 and 25, 2021. The authors have not received any funding or grants in support of the presented research or for the preparation of this work and have no declarations of potential conflicts of interest.

Corresponding author: Augusto Lauro, Department of Surgical Sciences, Sapienza University, Viale Regina Elena 324, 00161 Roma, Italy

E-mail: augusto.lauro@uniroma1.it

Table 1. Benign Hepatic Tumors Treatable With Liver Transplant